At its simplest, operetta is described as a genre of light opera, in terms of both music and subject matter. But of course it isn’t that straightforward. Where, for example, does this leave Mozart’s lighter comic pieces such as Die Zauberflote (The Magic Flute, 1791) or Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore (The Elixir of Love, 1832)?

The dividing line between opera and operetta isn’t hard and fast, but keeping that in mind it is still possible to make some distinction. It’s easier to say what operetta is than what opera isn’t, so that’s where we’ll begin.

Operettas contain spoken dialogue and often dancing; however, they differ from musical theatre in that the singing remains prominent, whereas in musicals the dialogue comes to the fore. Operettas tend to be shorter and less complex than traditional operas and are often (but not always) sung in English.

The subject matter is almost always humorous, with plots bordering on the absurd. Romance, mistaken identities, cross dressing and confusion are the order of the day, but all with a neat resolution and a happy ending – unlike traditional operas. Notable composers of operettas include Offenbach, Johann Strauss, Lehár and Gilbert and Sullivan.

All of this makes operetta an excellent introduction to the artform for the uninitiated. Even those who claim to hate opera or to not even be able to name one will likely have a favourite operetta. Gilbert and Sullivan’s incredibly well-known pieces are cases in point. The duo wrote 14 operettas together, including The Pirates of Penzance (1880), The Mikado (1885) and HMS Pinafore (1878) – all of which remain hugely popular.

Watch the Wichita Grand Opera perform Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance, filmed on 8 May 2008.

However, these same properties have led to the charge – from some quarters – that operetta is simply ‘opera lite’. That it is a lesser artform and not as worthy as its more serious older sibling. But is this really fair?

It is true that operetta asks less of its audience in both scale and score. However, going back to Gilbert and Sullivan, their witty, satirical productions might seem like simple light-hearted entertainment but there’s usually more going on. Tongue-twisting lyrics and absurd plots combine to provide an often biting comment on the social mores of the day.

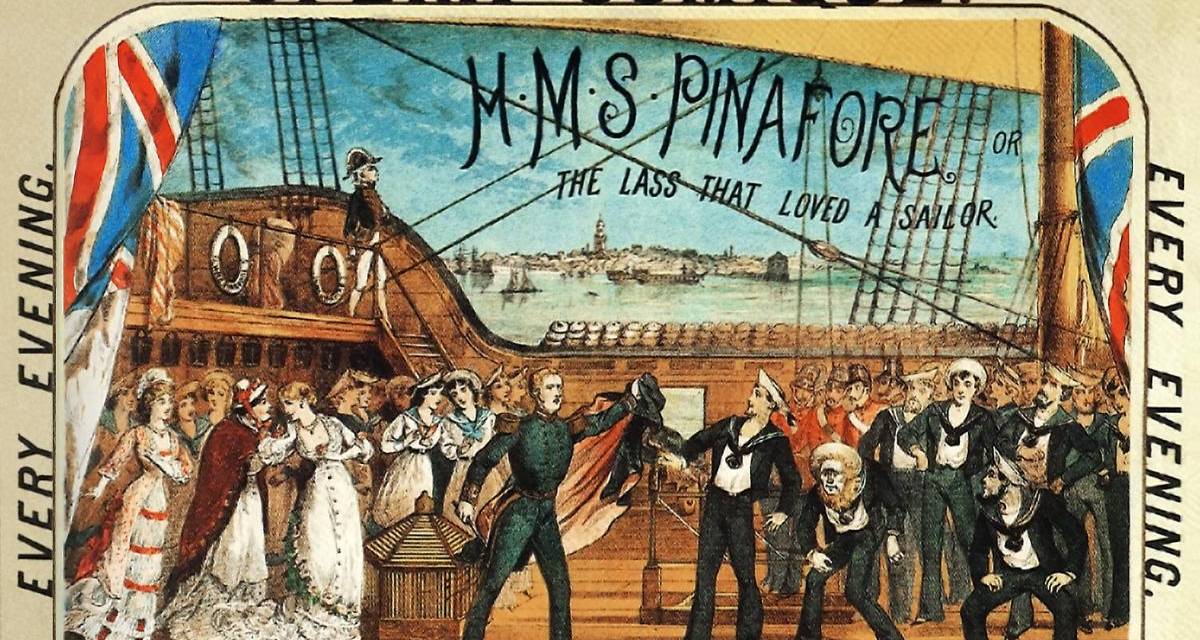

HMS Pinafore, for example, uses the devices of babies accidentally swapped at birth, the regimented hierarchy of the Royal Navy and love between different social classes to lampoon the British class system, patriotism and politics. The operetta has a happy ending in which everyone’s true identity is revealed and the lovers are allowed to live happily ever after.

Operetta might overturn many of opera’s traditions – giving the protagonists a happy ending, for example – but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t tackle the big questions.

None of which answers why the comedic operas of the likes of Mozart,Donizetti and others aren’t considered operetta. Partly, this is about timing. Operetta originated around the middle of the 19th century to satisfy a desire for short, light works in contrast to the full-length entertainment of the increasingly serious opéra comique. A genre of French opera, the term ‘comique’ was increasingly misleading and represented something closer to ‘humanistic’, meaning that such productions portrayed real life, rather than being based on myth or legend.

The starting point for this new French musical theatre tradition was Don Quichotte et Sancho Pança, which premiered in 1848 and has been described by composer Reynaldo Hahn as “simply the first French operetta”. It was written by the French singer, composer, librettist, conductor and scene painter Hervé (real name Louis Auguste Florimond Ronger). He is often considered to be the grandfather of operetta.

It was French composer Jacques Offenbach who made operetta an international artform. He composed more than 100 operettas in the 1850s to 1870s and was a powerful influence on later composers of the operetta genre, particularly the younger Johann Strauss and Arthur Sullivan. In 1858 he produced his first full-length operetta, Orphée aux enfers (Orpheus in the Underworld); exceptionally well received, it has remained one of his most played works.

It would be anachronistic to call operas composed before around 1848 operettas. But it’s also probably true that a certain amount of snobbery is involved. There are plenty of comic works composed after this date aren’t thought of as operettas. These might be longer than a traditional operetta, but other than that are very similar in subject and style.

Verdi’s Falstaff, which premiered in 1893, is referred to as comic opera rather than operetta. The plot revolves around the thwarted, sometimes farcical, efforts of the fat knight Sir John Falstaff to seduce two married women to gain access to their husbands’ wealth. Verdi was known for his tragedies – of his 28 operas only two are comedies. Falstaff was the second, written when the composer was approaching 80; he had previously claimed that he longed to write another light-hearted opera.

Some opera purists might insist that these works – by ‘serious’ composers – are operas because operetta isn’t real opera, that it is more akin to musical theatre. Operetta is seen as something less worthy than ‘true’ opera, but I think we’ve seen that this is unfair.

While operetta is distinguished from opera, the dividing line may not be as hard and fast as some might like to claim. With its lighter subject matter and shorter works, operetta remains a popular choice among even those who think they don’t enjoy opera and it provides an excellent introduction to the artform.

Image

An illustration of a scene from HMS Pinafore from the original theatre poster and playbill created for the original production in 1878 at the Opera Comique in London (D’Oyly Carte Company, Wikimedia Commons).

Very interesting. I am a musician, but am writing a novel, at this time about Black soloists not being offered parts in operas, no matter how good they are. Not since Marian Anderson have Blacks been considered for roles. The character is writing an operetta/opera. Now to find out the operetta vs musical.a