The venue in which you experience an opera informs that experience. I don’t say this to be controversial, and I certainly don’t mean that opera can only be enjoyed at the world’s most exclusive opera houses. What I mean is that place – the physical environment – affects our enjoyment of an opera.

Think about food, for example. A cheese sandwich grabbed at your desk between meetings is a very different experience from that same cheese sandwich shared with a group of friends reclining on a hand-crocheted blanket in a sun-lit park. I’m choosing my words very deliberately here, but you get the point: context counts.

London’s Royal Opera House (ROH) is without a doubt an imposing building, from its Doric-columned front to its chandeliered marble interior. It’s also huge, housing two full-size stages, as well as bars, restaurants, rehearsal spaces and more. If you wanted to impress a first-time visitor to London you could do a lot worse than taking them there.

The 2,256-seater main auditorium is Grade II listed and really is the ideal space to stage the most opulent of operas. The sheer size of the place gives producers and designers a free rein to create almost anything, while its long and distinguished history provides a pedigree that you just don’t get anywhere else.

This isn’t to say somewhere like the opera house is the only, or even the best, place to experience the artform.

In its early days opera was staged in the homes of the aristocracy. It would have been a much more intimate affair, but also much more about impressing visiting dignitaries with one’s wealth and taste, rather than watching the performance. It was with the opening of public opera houses, with paying audiences, that what was happening on stage came to the fore. This perhaps harking back to the days of ancient Greek tragedies, which were often didactic pieces performed in open-air auditoriums.

Where an opera is staged presents both problems and opportunities for creative teams and performers. Consider La bohème (The Bohemians, Puccini, 1896). The opening scenes of Act II in which our four poverty-stricken artists celebrate their unexpected windfall, are stunningly realised in Richard Jones’s many times revived production for the Royal Opera House.

It’s the perfect setting to show off the wealth and glamour of the setting: the opulent costumes and scenery, the children’s chorus, the huge number of extra performers, the glitz of Paris’s shopping arcades. It contrasts perfectly with the intimacy of the closing scenes of Act I between Rodolfo and Mimì. Designer Stewart Laing really made the most of the space with his stage and costume designs.

But those intimate scenes present their own challenges – how to make such an open space seem small and intimate, for example. Laing solved the problem by going minimal and it worked. But imagine such scenes performed in a beautifully decayed former church.

This is exactly what Northern Ireland Opera did when the company returned to live performance following coronavirus lockdowns in the country. It chose to stage its new production of Puccini’s classic in the Carlisle Memorial Church, an iconic former place of worship in Belfast. Closed for worship in 1980, the church had been in a derelict condition until it was brought back to life as an arts venue for the community.

The atmospheric, dilapidated interior of the church is the ideal setting for the artists’ freezing, rundown garret. These imaginative, site-specific stagings are really exciting and something I hope will happen more often. Think how wonderful a production of Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges (The Child and the Spells, 1925) staged in a country house would be. Audience and performers could move between the child’s bedroom to the gardens and then back inside the house for the finale.

Opera is often accused of being elitist, and not without some justification when you consider that top-price tickets at the Royal Opera House can set you back £250. But such site-specific stagings, taking opera out of the opera house, can help to dispel that criticism. They are much more inclusive, helping to remove the stiff formality of many an opera house, while also allowing for a lower price point.

But the true heroes of inclusivity are pub theatres. I genuinely love pub theatres, and not just for opera, but all kinds of productions. These are generally small, intimate spaces that are very informal, making them ideal for anyone who feels out of place in the grander venues. They also change the experience of being at the opera. It’s just more fun.

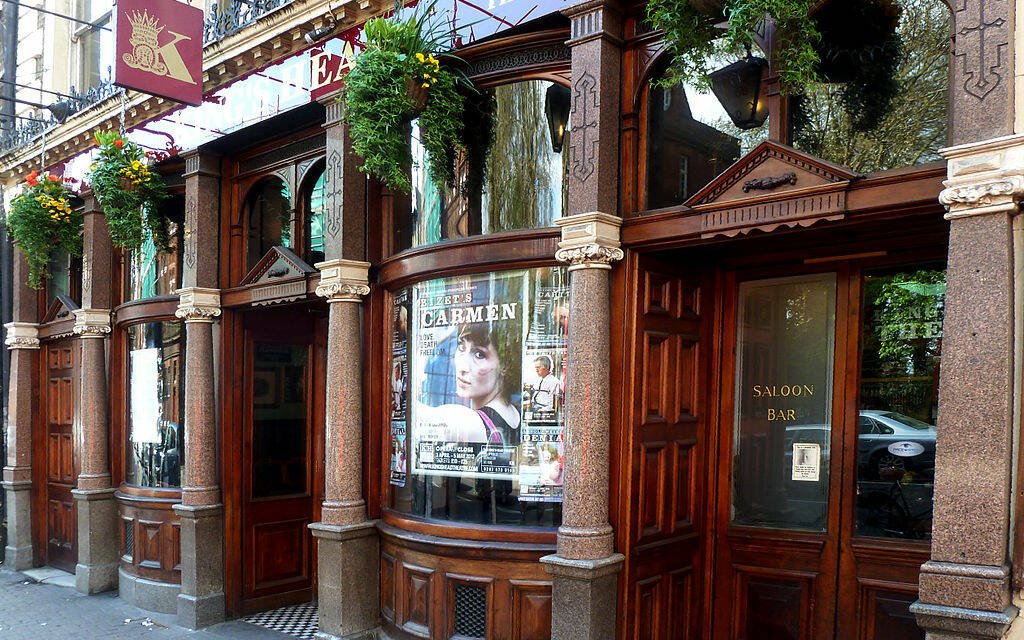

They’re ideal for pared-down productions that really get to the heart of an opera or for trying something new. I saw an excellent version of Carmen (Bizet, 1875) at the King’s Head Theatre, a room at the back of an Islington pub of the same name. With just three cast members – playing Carmen, José and Escamillo – it was about as stripped back as possible.

Sung in English, it featured a brand new libretto by Mary Franklin and Ashley Pearson which brought the story bang up to date with Carmen a cleaner for the NHS, José a nurse and Escamillo a footballer. It was excellent, with the set and sound designers, music and movement directors and performers all making the most of the space they had. But it wouldn’t have worked in an opera house.

And that’s the point. Place matters. Not because opera only belongs in the opera house, but precisely because it doesn’t. The physical space in which an opera is staged will change our experience of that opera, and when it’s used well it will only enhance it.

Image

The King’s Head pub in Islington, north London, plays host to King’s Head Theatre, an innovative company that produced an excellent stripped-down version of Bizet’s Carmen. It’s a very different experience from Carmen at the Royal Opera House (Oxfordian Kissuth, via Wikimedia Commons).