One of the biggest problems facing opera in the UK is language. A British Council survey found that 62% of the population only speak English. Compare this to the EU as whole, where 56% of people speak at least two languages. Most operas are sung in languages other than English, usually Italian, French or German, and for us linguistically challenged Brits this can be off putting.

There are, of course, plenty of operas written in English; the works of Gilbert and Sullivan and Benjamin Britten come to mind. In addition to this is the practice of translating the great operas into English. This brings with it a whole host of pros and cons.

For an English-speaking audience, the benefit of translation to English is obvious. It means we can understand what’s being sung. We can follow the story and appreciate what’s going on. This makes some of the world’s greatest operas much more accessible and forms the English National Opera’s mission to make the highest-quality productions open to everyone.

The company states: “We sing in English and believe that singing in our own language connects the performers and the audience to the drama onstage, and enhances the experience for all.”

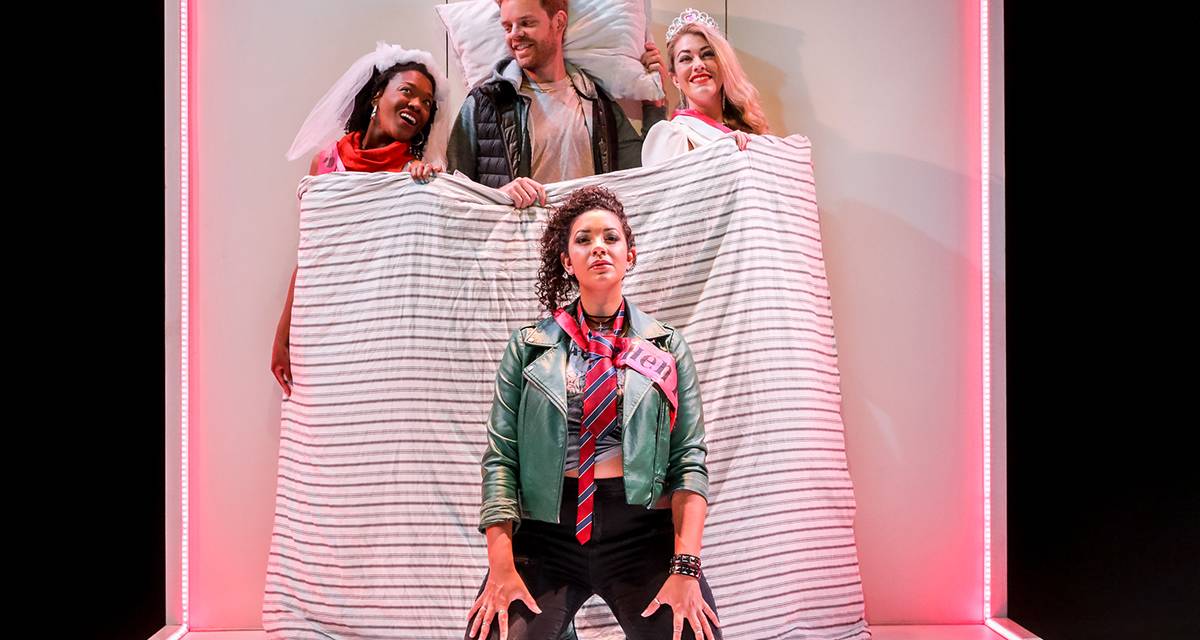

This is a philosophy we at Opera For All agree with. I saw a modern, English version of The Magic Flute (Mozart, 1791) by Opera Up Close at Soho Theatre in 2017. I don’t know any German and while I am familiar with the story, hearing it in my native tongue meant I could relate to it in a way I can’t when listening to productions in their original language.

As with any translation, a sensitive rendering will remain true to the composer’s and the librettist’s original aims. This is tricky in any media, but especially so with opera, in which it’s not just a case of sticking to the meaning. Any translator must also consider how the finished piece will sound. They have to think about rhythm, tempo and even the sounds of individual words and how they combine.

Think how different the phrase ‘good day’ sounds in English, French (bonjour), Italian (buongiorno) and German (guten Tag). We rarely say ‘good day’ in English these days, so would ‘hello’ make a better substitution? The phrase has two syllables in English and French but three in Italian and German, changing the rhythm, while the German has a more guttural sound than either French or Italian. All of this affects the final translation, which in turn will affect the audience’s understanding.

In order to ascertain the original aims, the translator must turn to the libretto. This can be of varying help. Some contain precise stage directions, others none at all. In the latter case the translator can only rely on the words and the score, interpreting what they read. Any translation is also an act of interpretation and therefore highly subjective.

Opera purists might argue that this makes translation impossible and that all productions should be heard in their original language. And maybe they have a point. It’s true that sound, meaning, rhythm, tempo, music and more all combine to create the full experience and much of this is lost in translation.

But it is exactly this attitude that leads to charges of elitism in opera and if the artform is ever to shake off such criticisms it needs to be accessible to all audiences. A good translation can preserve the original intentions of the composer and librettist, while making the production so much more enjoyable for the audience. This is especially true for newcomers – watching an opera in your native tongue will only enhance your experience, and when you see it again in the original language you can fully appreciate the meaning.

Image

Abigail Kelly, Peter Kirk, Fleur de Bray and Felicity Buckland in Opera Up Close’s English-language version of The Magic Flute (Andreas Grieger).