We all know that the composer writes the music, and many composers are well known. But even the greatest operas would be nothing without the story and the words. So where do these come from?

Very simply, the librettist is the writer of the libretto (plural: libretti), the diminutive for libro, or book in Italian – literally ‘little book’. Libretto can refer to either the actual text or words of an opera or the book in which these words are published. The librettist, therefore, is the book writer.

Musical theatre has a composer writing the music, a lyricist writing the song words and a librettist writing the spoken dialogue and directing the order of the songs and incidental music. Opera, in which all the dialogue is sung, has only a composer and librettist. It’s a complicated job that involves much more than just writing song lyrics, and the libretto will contain the opera’s story and stage directions as well as the sung dialogue.

The stories themselves are often adapted from mythology (Wagner’s Ring Cycle, for example), older plays (Shakespeare is a popular source, giving us Britten’s Midsummer Night’s Dream (Britten, 1960) among others) and history (Rhondda Rips It Up (Langer, 2018), a feminist opera based on the life of suffragette Margaret Mackworth, the second Viscountess Rhondda).

A great number of composers are household names, but this generally isn’t the case with the librettist. You don’t need to be an opera aficionado to have heard of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. But what about Emanuel Schikaneder? He wrote the libretto for Mozart’s celebrated opera Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute, 1791), as well as 55 other libretti. It’s fair to say that his is not a well-known name outside of opera circles. An exception to this is writing partnerships, one of the most famous of which being Gilbert and Sullivan. Arthur Sullivan composed the music for the pair’s 14 comic operas, while William Gilbert wrote the libretti.

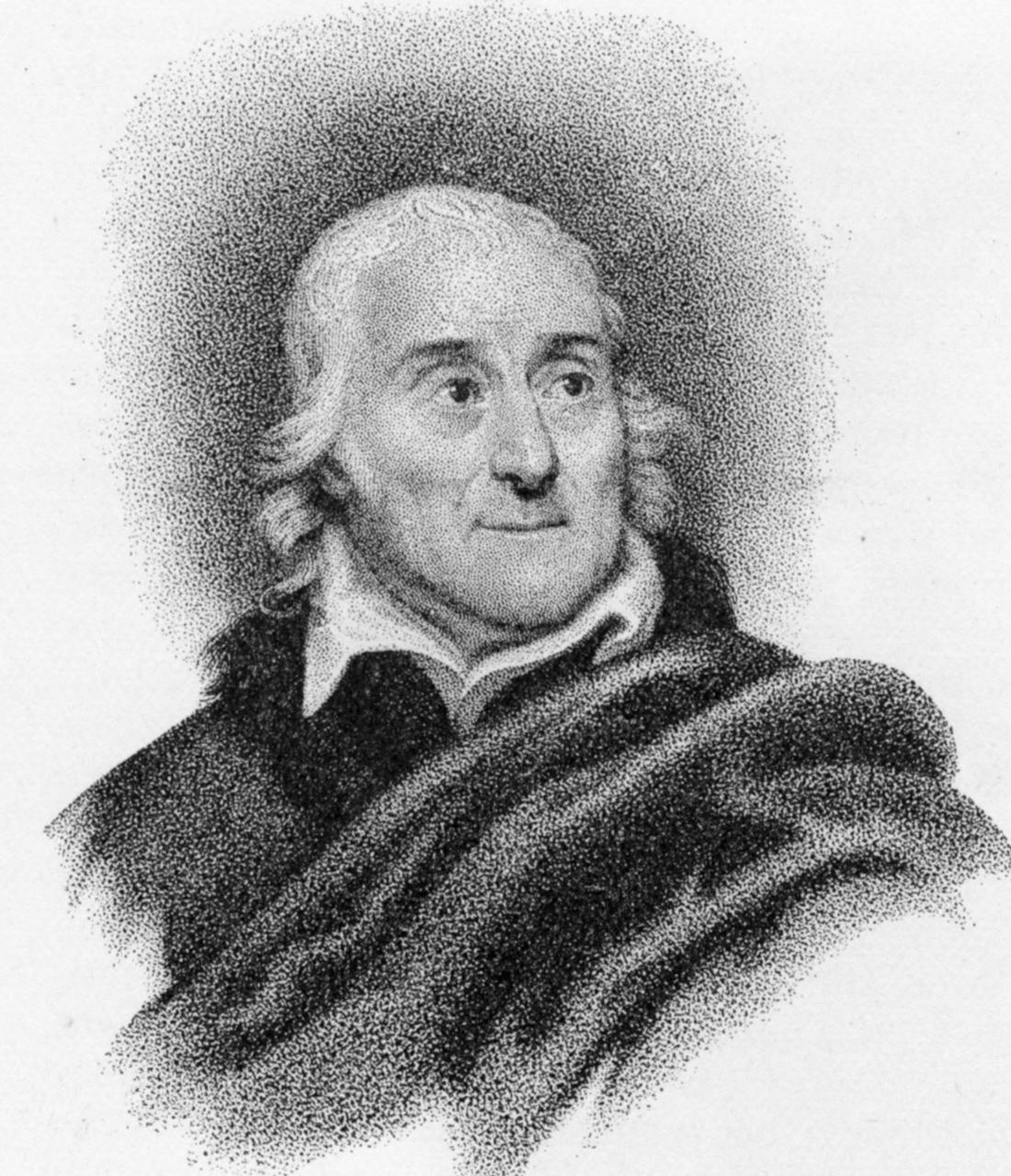

There are several 17th century operas for which the name of the librettist wasn’t even recorded, while the composer became famous. It’s hard to say exactly why composers have traditionally taken the limelight, but one explanation is that the music is thought to be more complex than the words, much of which might have been lifted from an existing play or story. This isn’t true for all librettists, though. Lorenzo Da Ponte, for example, was a noted 18th century librettist who wrote libretti for 28 operas, including three of Mozart’s most celebrated pieces, Don Giovanni (1787), Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro, 1786) and Così fan tutte (Women Are Like That, 1790).

The ways in which composers work with librettists differ. Gilbert and Sullivan’s own relationship was famously contentious, and after the failure of The Grand Duke in 1896 they never worked together again. Some composers wrote their own libretti; Wagner is the most famous of these. He sought to synthesise the poetic, visual, musical and dramatic arts, with music subsidiary to drama; he referred to this concept as the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. In other cases the libretto is written in close collaboration with the composer, which can involve both writers adapting and commenting on each others’ work.

However the librettist creates their work, though, and regardless of whether we believe the music to be prominent, it is still true that the operas we know today wouldn’t be what they are without the words. So maybe it’s time for the librettist to take a bow.

Images

From top:

Libretti (left to right): I Medici; composer Ruggero Leoncavallo also wrote the libretto. Cavalleria rusticana (Rustic Chivalry), composed by Pietro Mascagni to an Italian libretto by Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti and Guido Menasci. Tosca by Giacomo Puccini to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa.

Lorenzo Da Ponte was an Italian librettist who wrote the libretti for 28 operas by 11 composers.

All images public domain via commons.wikimedi.org.