Libretto – plural libretti – is Italian for ‘booklet’ or ‘small book’; it is the diminutive of the word libro (‘book’). It is the full text used in a dramatic musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. It is sometimes also used to refer to the text of major liturgical works, such as the Mass, requiem and sacred cantata, or the story line of a ballet. In modern musical theatre, it is often referred to as ‘the book’, whereas in opera the Italian term is almost always used.

The libretto contains all the words of the show, both written and sung, along with stage directions. Opera libretti are generally written in verse, although musical theatre and some modern operas are prose. The libretto is created by the librettist, who is generally different from the composer, although this isn’t always the case – Wagner famously wrote his own libretti.

While libretti can be original, many are based on older sources. Wagner, for example, drew inspiration from Norse mythology. Medieval history (Philip Glass’s text for his own Akhnaten (1984), for example), Greek mythology (Italian poet Calzabigi’s libretto for Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (1762)), ancient legends and folktales (such as Victor-Joseph Étienne de Jouy and L F Bis’s French-language text for Rossini’s William Tell (1829)) have all been mined for subject matter.

The works of playwrights and poets have provided a rich vein of material, with Shakespeare being a popular source. Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest and Othello have all been adapted for opera, while the libretto for Verdi’s Falstaff (1893), written by Italian poet and novelist Arrigo Boito, was based on The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Often the same work will be the base for several operas. Le Barbier de Séville ou la Précaution inutile (The Barber of Seville or the Useless Precaution), a French play by Pierre Beaumarchais, has been adapted many times, with the most famous being Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville, 1816); the librettist was Italian writer Cesare Sterbini.

Writing for opera – or any piece of musical theatre – is a very different process to writing spoken drama. Elaborate literary devices, metaphor, complex concepts and so on are difficult to convey in song and would either be lost or simply confuse the audience, not to mention be incredibly hard to sing.

Music moves at a much slower pace than speech, while emotions that would need to be made explicit in spoken drama can be communicated by the orchestra. The use of simple words and repetition of phrases help to increase understanding. Ideally, music and text will work together to tell the story, and this can require a lot of amendments to both in order to create a harmonious performance.

Libretti were, quite literally, small books. In its early days, starting with Dafne by composers Jacopo Peri and Jacopo Corsi, with a libretto by Florentine poet Ottavio Rinuccini, opera was a court entertainment and the words were printed in small books as a commemoration of the performance.

The first libretti were printed in small quarto format. This format of a book or pamphlet is produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, which is then folded twice to produce four leaves. It measures about 25cm by 20cm, or slightly smaller than a sheet of A4. A libretto typically contained between 12 and 20 leaves.

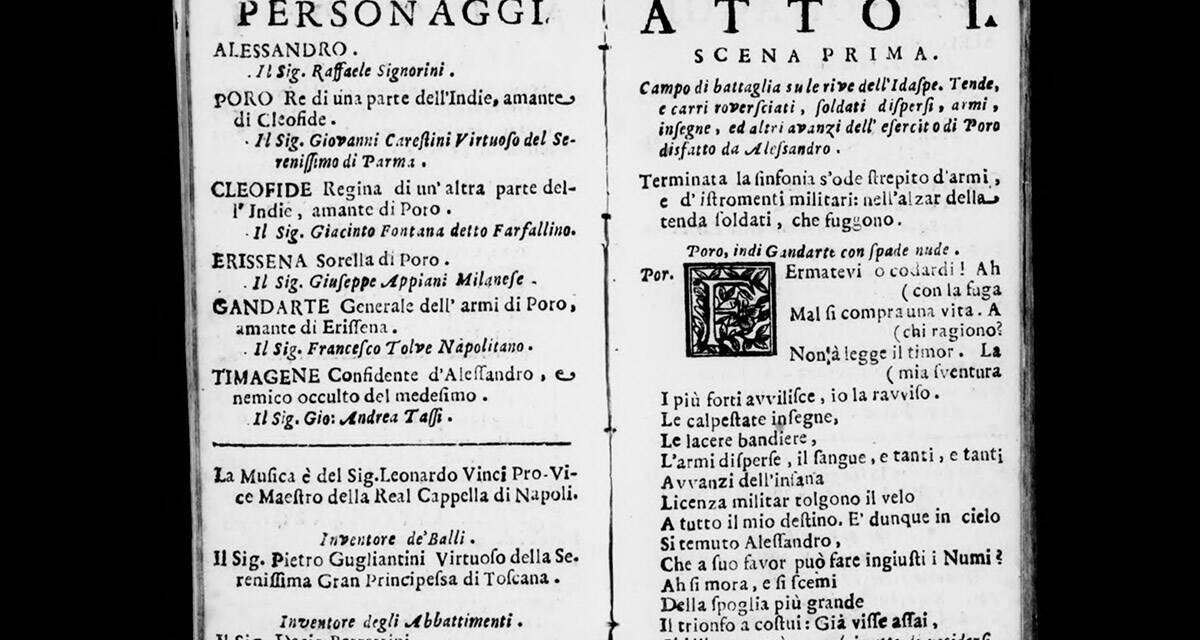

Dafne was first performed at Carnival in Florence in 1598; the libretto was published by Giorgio Marescotti in 1600. The title page names the author of the libretto, the sponsor of the performance (Jacopo Corsi), the person in whose honour it was given, the place and date of publication and the publisher. In addition to the words, it also features a list of characters and brief stage directions.

As opera became more of a public spectacle, audiences used libretti to follow the story. As a result, more information began to be given, with detailed stage directions, a synopsis of the plot and an address to the reader, which was often written by the librettist. Lists of scenes and of machines and effects used might also be included.

Later libretti also featured cast lists and named the musical director, costume designer, producer, copyist, orchestral principals, chorus and even – very occasionally – the understudies. Some special performances required more sumptuous publications, often illustrated with scene designs.

These printed libretti are a hugely important source of information for opera historians, providing detailed and reliable data on individual works. They are often the sole surviving record of an opera, especially the older ones. They are also used by modern-day producers to create productions as close as possible to the original intentions of the librettist and composer.

Today, many libretti are easily found online, often for free. They include the full text in the opera’s original language as well as an English translation. They provide an invaluable introduction to opera, so it’s always worth searching for one and reading it prior to seeing an opera, especially if it’s one that’s new to you.

Image

Alessandro nell’Indie (Alexander in India) is a libretto in three acts by Pietro Metastasio. It was set to music around 90 times, firstly by Leonardo Vinci, whose version premiered in Rome 1730 (via Wikimedia Commons).